Fermentation is pivotal in the sourdough process, making it tastier and healthier than yeasted bread. Unlike yeasted bread, which relies on commercially produced yeast for rising, sourdough utilizes natural fermentation from wild yeasts and bacteria present in the environment.

These wild yeasts and bacteria are contained in your sourdough starter. A starter, in the context of sourdough baking, is a mixture of flour and water that has been allowed to naturally ferment, capturing wild yeasts and bacteria. This living culture is what gives sourdough its distinct flavor and characteristics.

The starter comprises a stable mix of yeast and lactic acid bacteria. Together, they consume the sugars in the flour, yielding the notable health and flavor benefits of sourdough. In this chapter, we’ll explore baking from the perspective of fermentation. We’ll delve deeper into the composition of a starter, examine the functions of each component, and uncover the reasons behind sourdough’s delectable appeal.

Figuring out what causes bread to have its flavor is an active area of research, and if you read any papers on the subject you’ll be barraged with the names of chemicals. Over 540 molecules that give sourdough its flavor have been discovered (Ptel, Onno & Prost, 2017). To pull a handful at random (Hansen & Hansen, 1996): 2-methyl-propanal, 3-methyl-butanal, isopentanal, 2-nonenal, benzylethanol, 2-phenylethanol, dimethyl sulphide and 2-furfural.

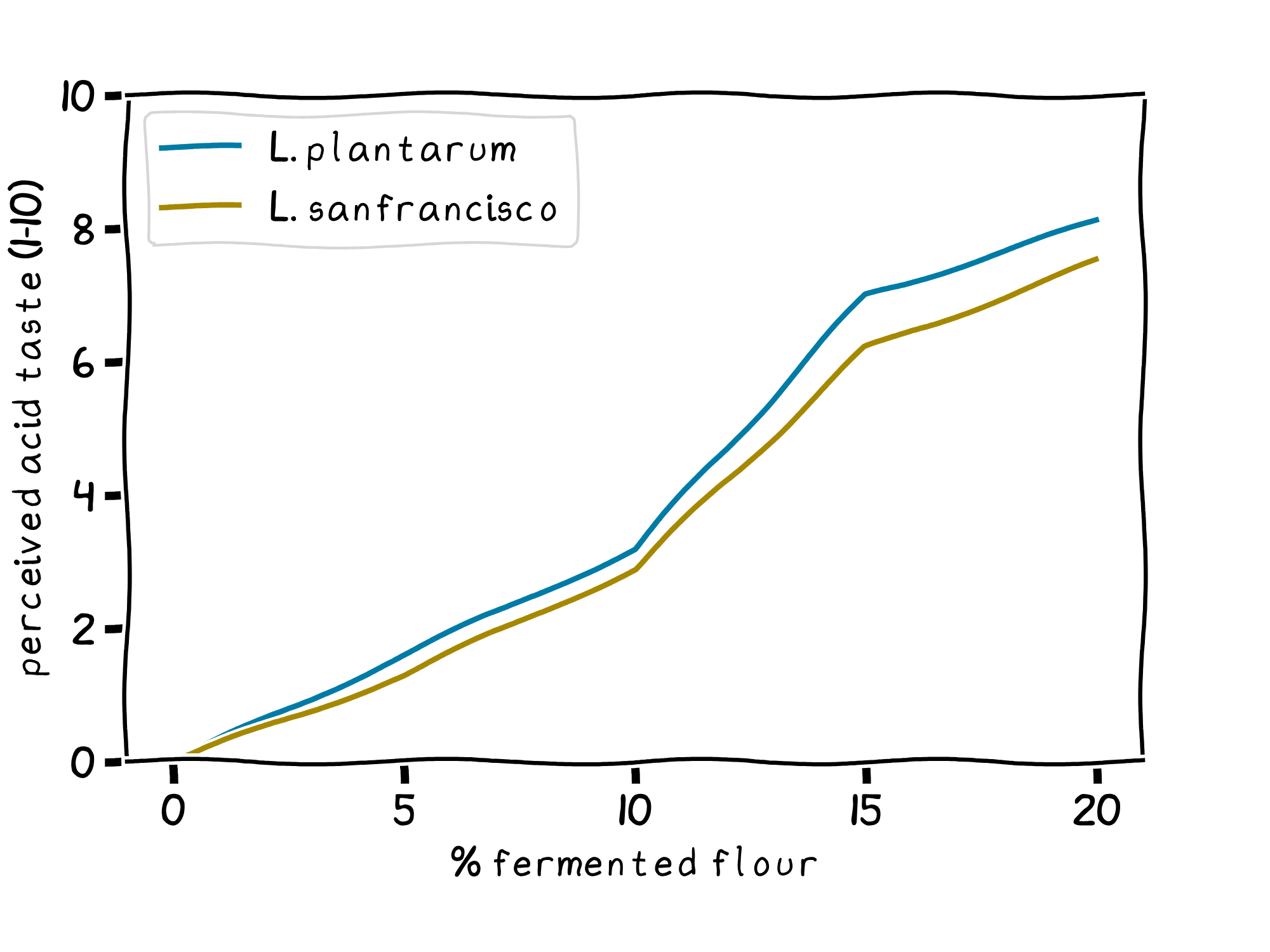

As a simple demonstration that sourdough fermentation impacts the taste of bread, the following graphs shows results from Hansen & Hansen 1996. In this study, a panel of tasters placed the acidity of bread on a 1-10 scale. There is a clear positive correlation between the acidity of the bread and the percentage of sourdough used in the bak. The more sourdough, the more sour the bread.

Other studies have focused on how sourdough improves the taste of bread and, indeed, use of sourdough can improve the flavor of bread. The flavor of sourdough wheat bread is richer and more aromatic than wheat bread, and tasters in this study preferred breads baked with 5-10% sourdough by weight, characterized by the following adjectives.

| Yeasted Bread | Sourdough Bread |

|---|---|

| Flour | Mild Sour |

| Sweet | Fresh |

| Yeasty | Aromatic |

How does a sourdough starter add flavor

A sourdough starter is a symbiotic culture, often comprised of 1-3 species of yeast and an additional 1-5 species of lactic acid bacteria. These microorganisms coexist, each playing a pivotal role in the fermentation and flavor development of the bread. Originating from a simple mixture of flour and water, a starter captures wild yeasts and bacteria from its environment, which then thrive and multiply in the mixture. Over time, with regular feeding of flour and water, this living culture becomes a stable and active fermentative force.

When dough is mixed and water is introduced, it hydrates the flour, initiating a fascinating sequence of biochemical reactions.

Water Helps Enzymes Get to Flour

Yeast eats sugar. Flour contains only a few percent sugar by weight. Nowhere near enough to grow all that yeast, so what happens?

Flour contains an enzyme named amylase. When the flour is mixed with water, the amylase becomes active. Amylase begins to break down the starches in the flour into sugars that are the perfect food source for yeast and bacteria.

So at this point, the yeast and bacteria are in contact with a food source, and they start doing their thing: eating

Microbes eat the sugar

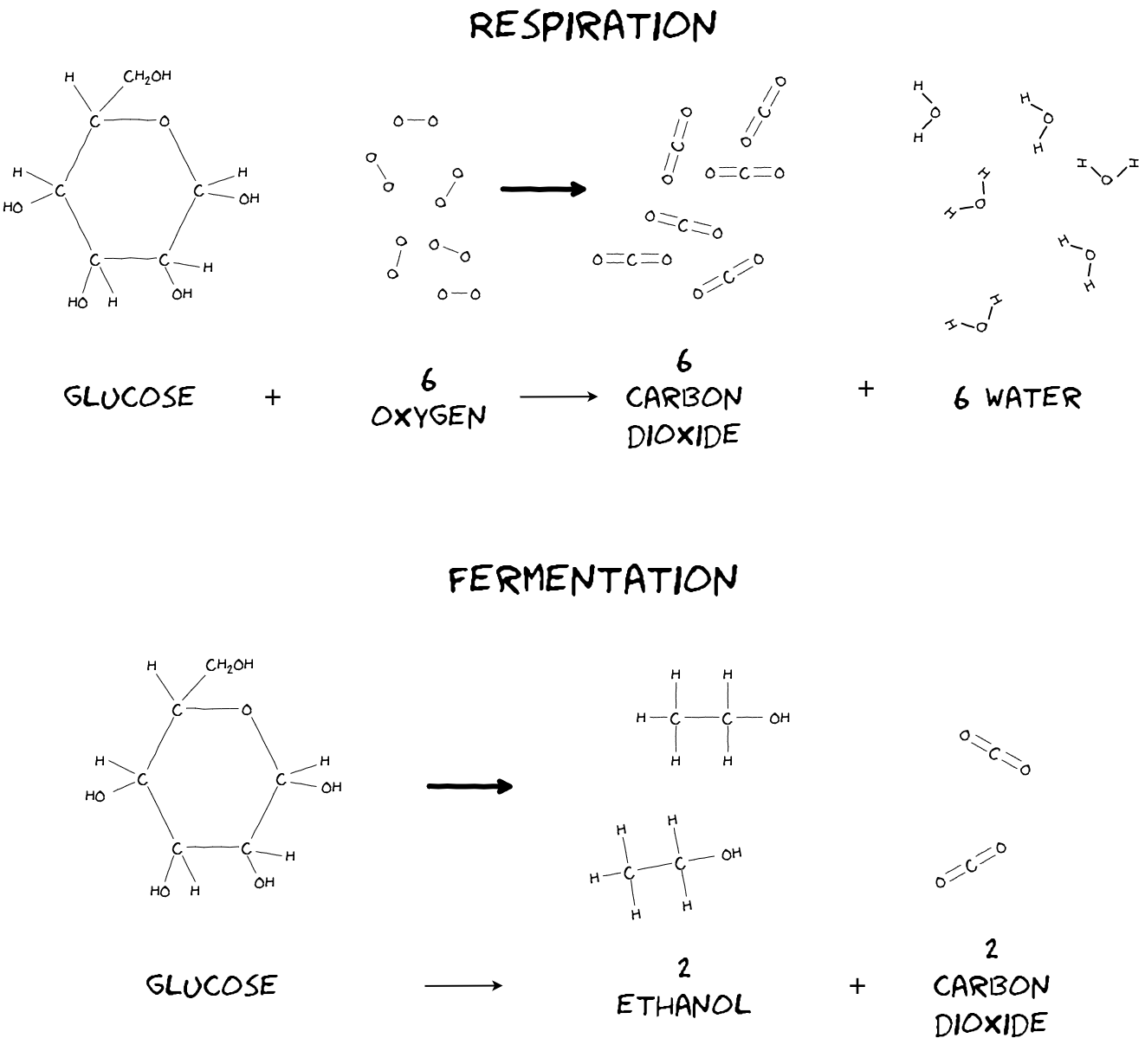

We’ll start by talking about yeast, since this is what people are usually associate with bread baking. Yeast can do two things: respiration and fermentation. When the yeast has the choice, it will respire. In respiration, the yeast takes food (glucose), and oxygen molecules (O2). It turns these into carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O). In this way the yeast can effectively use up almost all the oxygen inside the dough.

When conditions become less suitable for respiration (which happens if the yeast is in a low-oxygen environment or has enough glucose), yeast switches to doing fermentation. Here it turns glucose into ethanol and CO2. Yeast can transform 95% of fermentable foods in flour into ethanol, ethanol is either converted into flavor compounds during fermentation, or boils off during cooking since the boiling point of ethanol is 173°F, while the typical temperature of the center of a loaf of bread after baking is 190°F. Ethanol will also be converted into flavorful compounds during the fermentation process (See the next section))

The CO2 is what inflates bubbles in the dough. If you want to clearly demonstrate to yourself that yeast creates carbon dioxide, you can perform a simple experiment, simply feed your starter, take a sample of that and put it in an airtight Ziploc bag. After a few hours you’ll see that the bag is noticeably puffy, and a few hours after that it should have undergone a significant amount of inflation.

Turning Booze into Flavor

That there is alcohol in breads is a fact that was widely appreciated since at least the 1920’s. Sandwiched in the Canadian Medical Association Journal from November 1926, between a report about tuberculosis vaccine tests in monkeys and a story stating that “A proton, the heart of an atom, would look like a porcelain doorknob if we could see its sphere of influence” is the following

Professor Nicholas Knight and Miss Violet Simpson, chemists at Cornell College, Iowa, reported to the American Chemical Society that they had collected twelve samples of ordinary bread from bakeries and housewives' ovens and after chemical analyses found that the alcohol content of this prosaic food varied from .04 to 1.9 per cent, the latter quantity being well above the one half of one per cent limit set by the well-known prohibition statute.

Temperature is a critical factor in the fermentation process, influencing both the biochemical reactions and the resulting flavors in sourdough. A fermentation temperature of 41°F, commonly used in dough retarding, has been found to elevate the formation of esters, which are characterized by their fruity and pleasant odors during dough fermentation (Birch et al., 2013b).

Furthermore, the fermentation temperature directly impacts the fermentation quotient, a ratio of lactic acid to acetic acid. Higher temperatures tend to increase lactic acid production, thereby intensifying the acidification of sourdoughs (Brandt et al., 2004). Conversely, lower fermentation temperatures decelerate LAB acidification. In the presence of LAB, these cooler temperatures are conducive to yeast growth, ethanol and carbon dioxide production — the latter being essential for leavening — and the overall formation of flavor (Simonson, Salovaara, & Korhola, 2003).

Citations

- Birch, A. N., Petersen, M. A., & Hansen, Å. S. (2013). The aroma profile of wheat bread crumb influenced by yeast concentration and fermentation temperature. In LWT - Food Science and Technology (Vol. 50, Issue 2, pp. 480–488). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2012.08.019

- Brandt, M. J., Hammes, W. P., & Ganzle, M. G. (2004). Effects of process parameters on growth and metabolism of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis and Candida humilis during rye sourdough fermentation. In European Food Research and Technology (Vol. 218, Issue 4, pp. 333–338). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-003-0867-0

- Hansen, A., & Hansen, B. (1996). Flavour of sourdough wheat bread crumb. In Zeitschrift fur Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und -Forschung (Vol. 202, Issue 3, pp. 244–249). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01263548

- Pétel, C., Onno, B., & Prost, C. (2017). Sourdough volatile compounds and their contribution to bread: A review. In Trends in Food Science & Technology (Vol. 59, pp. 105–123). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2016.10.015

- Simonson, L., Salovaara, H., & Korhola, M. (2003). Response of wheat sourdough parameters to temperature, NaCl and sucrose variations. In Food Microbiology (Vol. 20, Issue 2, pp. 193–199). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0740-0020(02)00117-x