Fermented foods, sourdough included, have undergone an explosion in popularity in recent years. This was driven in part by their proposed health benefits (see e.g. Dimidi et al., 2019 for a review).

Sourdough has definite health benefits over yeasted breads. The beneficial effects of eating sourdough are due to the effects of fermentation by the yeasts and bacteria on the dough. Here we summarize a few of the health benefits of sourdough bread relative a more standard yeasted bread.

It has a lower glycemic index

The Glycemic index (GI) of food is a ranking based on its immediate effect on blood glucose levels. Foods with lots of easily digestible carbohydrates have a high GI, and after they’re eaten, they spike levels of blood sugar significantly. Foods with a lower GI release their energy more slowly. Although GI is only one component of the overall healthfulness of a food, some research has linked high GI diets with a greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes (Bhupathiraju et al., 2014), higher cholesterol levels (Fleming & Godwin, 2013), and more heart disease (de Rougemont et al., 2007).

Foods can be broadly classified into three categories

- low GI (<55)

- medium GI (55–69)

- high GI (>69)

For reference, a whole meal bread without sourdough fermentation has a GI of around 70.

Although bread, by its nature will remain relatively high GI, it has been found that sourdough fermentation is able to reduce the digestibility of some starches (Ostman et al., 2002), and correspondingly reduces blood sugar and insulin responses when compared to yeasted bread (Liljeberg et al., 1995) and reduce its glycemic index (Stamataki, Yanni & Karathanos, 2017), with some studies indicating that depending on the precise formulation, the bread may end up with a GI around 40-60 (Novotni et al. 2010; Novotni et al., 2012).

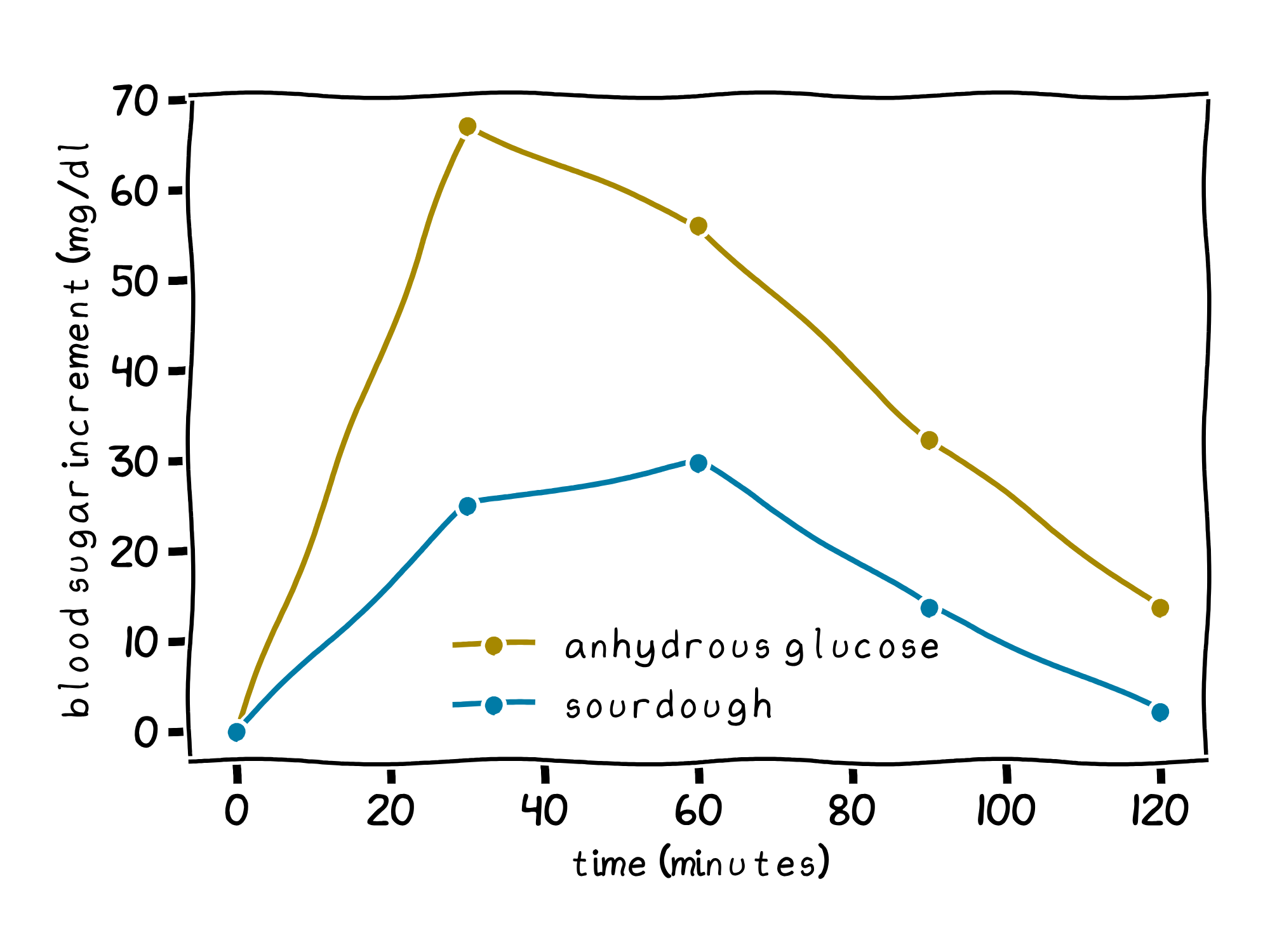

This is demonstrated in in the following image, which shows the measurement of the GI of some bread from (De Angelis et al., 2009). The two curves on this chart show the mean increase in blood sugar in 20 healthy volunteers after ingesting glucose, and after ingesting sourdough. The blood sugar increment is around 40.1% of that of pure glucose (pure glucose has a GI of 100), so the GI of the sourdough is 41.1, a figure low enough to indicate that this type of bread could have significant health impacts.

It Increases Available Bioactive Compounds

Fermenting with sourdough improves the bioavailability (Katina et al., 2005), in particular, the addition of a sourdough fermentation phase more than doubled the availability of folates and phenolic compounds, and B-complex vitamins relative to yeasted bread. Folate intake is necessary for several processes in the body, and associations between low folate level and chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cognitive dysfunction have been reported (Ebara, 2017). Many studies have shown a strong and positive correlation between the presence of phenolic compound and the antioxidant effects of foods, which (among other things) to decrease inflammation in the body related with chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and diabetes (e.g. Eliassen et al. 2012)

It Has More Bioavailable Minerals

Phytic acid is a substance found in many plant-based foods, including wheat flour. Phytate is present in an amount of around 3 mg/g in refined flour, and 8.5 mg/g in whole wheat flour (Febles et al., 2002).

Phytate is commonly called an “anti-nutrient” because it tends to bind to common minerals, including iron, zinc, magnesium and calcium, meaning that they are unavailable for absorption into the body. A prolonged sourdough fermentation was found to decrease phytic acid levels by 62%, relative to only 38% for a more standard yeast-based fermentation process (Lopez et al., 2021). Thus, it should be expected that relative to other breads, sourdough is able to supply more of these vital minerals.

Conclusion

Sourdough bread isn’t just tasty; it’s also better for you than regular bread in many ways. Unlike other breads, sourdough doesn’t cause a quick spike in your blood sugar. This is great news for people who want to watch their sugar levels. Plus, it has more of the good stuff our body needs, like vitamins and other healthy bits.

What’s even better? Sourdough helps our body take in more minerals, like iron and calcium. This is because sourdough doesn’t have as much of a thing called ‘phytic acid’ which stops our body from using these minerals. So, when you choose sourdough, you’re not just getting a yummy slice of bread, but you’re also making a healthier choice!

References

- Bhupathiraju, S. N., Tobias, D. K., Malik, V. S., Pan, A., Hruby, A., Manson, J. E., Willett, W. C., & Hu, F. B. (2014). Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from 3 large US cohorts and an updated meta-analysis. In The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (Vol. 100, Issue 1, pp. 218–232). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.079533

- De Angelis, M., Damiano, N., Rizzello, C. G., Cassone, A., Di Cagno, R., & Gobbetti, M. (2009). Sourdough fermentation as a tool for the manufacture of low-glycemic index white wheat bread enriched in dietary fibre. In European Food Research and Technology (Vol. 229, Issue 4, pp. 593–601). Springer Science and Business Media LLC. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-009-1085-1

- de Rougemont, A., Normand, S., Nazare, J.-A., Skilton, M. R., Sothier, M., Vinoy, S., & Laville, M. (2007). Beneficial effects of a 5-week low-glycaemic index regimen on weight control and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight non-diabetic subjects. In British Journal of Nutrition (Vol. 98, Issue 6, pp. 1288–1298). Cambridge University Press (CUP). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114507778674

- Dimidi, E., Cox, S. R., Rossi, M., & Whelan, K. (2019). Fermented Foods: Definitions and Characteristics, Impact on the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. In Nutrients (Vol. 11, Issue 8, p. 1806). MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081806

- Ebara, S. (2017). Nutritional role of folate. In Congenital Anomalies (Vol. 57, Issue 5, pp. 138–141). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1111/cga.12233

- Eliassen, A. H., Hendrickson, S. J., Brinton, L. A., Buring, J. E., Campos, H., Dai, Q., Dorgan, J. F., Franke, A. A., Gao, Y., Goodman, M. T., Hallmans, G., Helzlsouer, K. J., Hoffman-Bolton, J., Hultén, K., Sesso, H. D., Sowell, A. L., Tamimi, R. M., Toniolo, P., Wilkens, L. R., … Hankinson, S. E. (2012). Circulating Carotenoids and Risk of Breast Cancer: Pooled Analysis of Eight Prospective Studies. In JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute (Vol. 104, Issue 24, pp. 1905–1916). Oxford University Press (OUP). https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djs461

- Fleming, P., & Godwin, M. (2013). Low-glycaemic index diets in the management of blood lipids: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In Family Practice (Vol. 30, Issue 5, pp. 485–491). Oxford University Press (OUP). https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmt029

- Febles, C. I., Arias, A., Hardisson, A., Rodrı́guez-Alvarez, C., & Sierra, A. (2002). Phytic Acid Level in Wheat Flours. In Journal of Cereal Science (Vol. 36, Issue 1, pp. 19–23). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcrs.2001.0441

- Katina, K., Arendt, E., Liukkonen, K.-H., Autio, K., Flander, L., & Poutanen, K. (2005). Potential of sourdough for healthier cereal products. In Trends in Food Science & Technology (Vol. 16, Issues 1–3, pp. 104–112). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2004.03.008

- Liljeberg, H. G. M., Lönner, C. H., Björck, I. M. E (1995). Sourdough Fermentation or Addition of Organic Acids or Corresponding Salts to Bread Improves Nutritional Properties of Starch in Healthy Humans. In The Journal of Nutrition (Vol. 125, Issue 6, pp. 1503-1511). https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/125.6.1503.

- Lopez, H. W., Krespine, V., Guy, C., Messager, A., Demigne, C., & Remesy, C. (2001). Prolonged Fermentation of Whole Wheat Sourdough Reduces Phytate Level and Increases Soluble Magnesium. In Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (Vol. 49, Issue 5, pp. 2657–2662). American Chemical Society (ACS). https://doi.org/10.1021/jf001255z

- Novotni, D., Ćurić, D., Bituh, M., Colić Barić, I., Škevin, D., & Čukelj, N. (2010). Glycemic index and phenolics of partially-baked frozen bread with sourdough. In International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition (Vol. 62, Issue 1, pp. 26–33). Informa UK Limited. https://doi.org/10.3109/09637486.2010.506432

- Novotni, D., Čukelj, N., Smerdel, B., Bituh, M., Dujmić, F., & Ćurić, D. (2012). Glycemic index and firming kinetics of partially baked frozen gluten-free bread with sourdough. In Journal of Cereal Science (Vol. 55, Issue 2, pp. 120–125). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2011.10.008

- Östman, E. M., Nilsson, M., Liljeberg Elmståhl, H. G. M., Molin, G., & Björck, I. M. E. (2002). On the Effect of Lactic Acid on Blood Glucose and Insulin Responses to Cereal Products: Mechanistic Studies in Healthy Subjects and In Vitro. In Journal of Cereal Science (Vol. 36, Issue 3, pp. 339–346). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcrs.2002.0469

- Stamataki, N. S., Yanni, A. E., & Karathanos, V. T. (2017). Bread making technology influences postprandial glucose response: a review of the clinical evidence. In British Journal of Nutrition (Vol. 117, Issue 7, pp. 1001–1012). Cambridge University Press (CUP). https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114517000770